Our Commitment to Civil Rights and Human Dignity

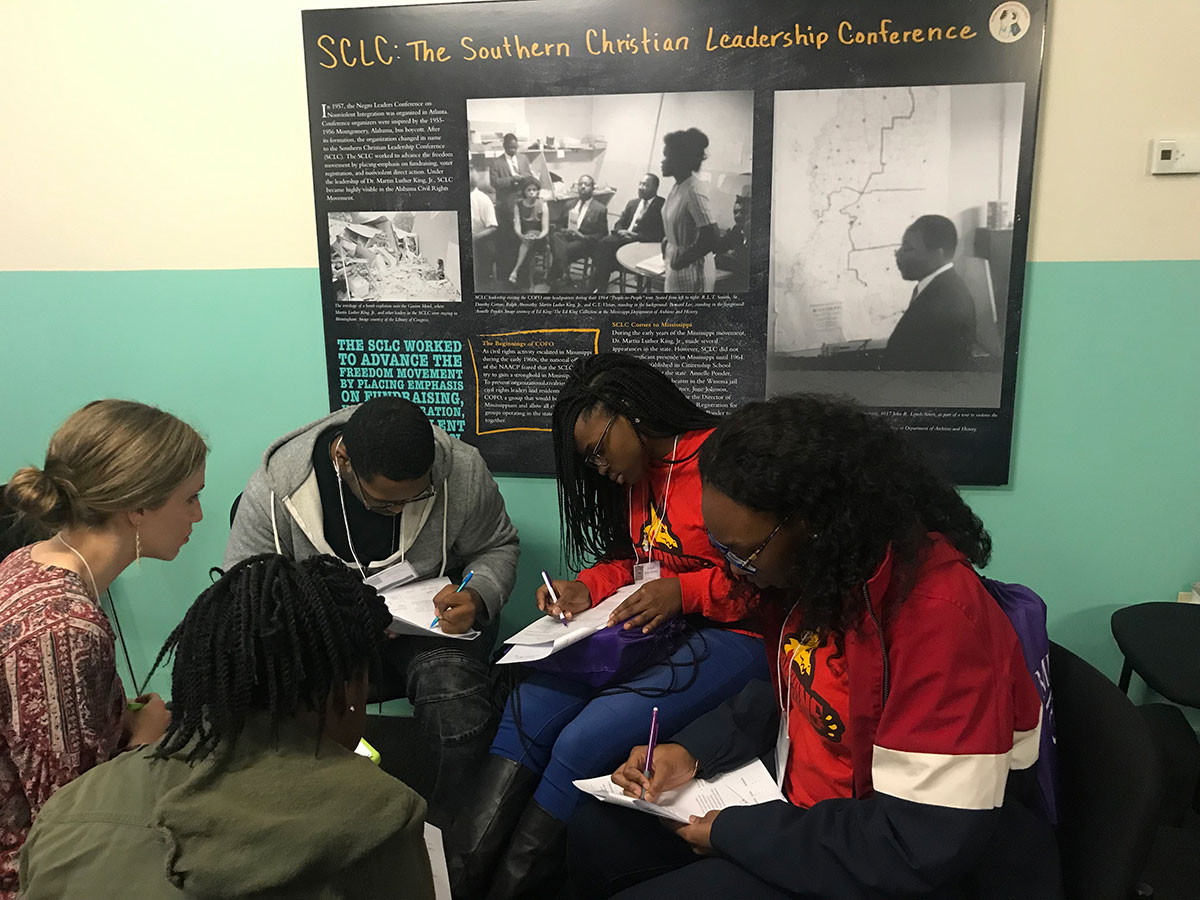

AP Physics students working in January 2019 at Jackson State University’s COFO Center for Civil Rights Education, which is housed in a building where Civil Rights leaders worked in the 1960s. The students are shown beneath a photograph of Dr. King working in that same room.

Our Commitment to Civil Rights and Human Dignity

The Global Teaching Project was created to advance a fundamental Civil Right—the right to a quality education—and we have made progress toward that goal. The Global Teaching Project has helped close educational disparities afflicting underserved rural, low-income, and minority communities by providing promising high school students access to rigorous courses that otherwise would be unavailable. We do so because we believe in the promise of America. Yet that promise is not evident to all, and is denied to some as a consequence of poverty, injustice, and even violence.

We join with those who honor the ideals articulated in our founding documents, and resolve to work to help make those ideals a reality for all Americans.

Read below for Full Statement

Four days before he died, Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his final sermon. Speaking at Washington’s National Cathedral, he decried the poverty that afflicted communities across America. Yet he singled out one town—Marks, Mississippi. He told the congregants, “I was in Marks, Mississippi, the other day, which is in Quitman County, the poorest county in the United States. I tell you, I saw hundreds of little black boys and black girls walking the streets with no shoes to wear.”

When visiting Marks, Dr. King wept at what he saw—hungry children housed in crude shacks and taught in dilapidated classrooms—images that stayed with him until the end of his life: “I can’t get those children out of my mind.”

Yet, over 50 years later, few Americans are mindful of communities like Marks, whose plight persists.

Over half the children of Quitman County, 55 percent, live in poverty, more than triple the national rate. Median household income is less than half the national level, and the lack of economic opportunity has led to rapid depopulation—Quitman County has fewer than half as many residents as when Dr. King walked its streets. And students in the Quitman County School District, which is 97% black, may graduate from high school without ever being in a class with a student of another race.

The death of Dr. King is widely characterized as marking the end of the Civil Rights Era, a period that, convention holds, began with the Brown decision and Montgomery Bus Boycott, continued through the 1963 March on Washington and 1964 Freedom Summer, reached its apotheosis with enactment of the Voting and Civil Rights Acts, and ended with assassination, protests, and riots.

We must reject the notion that the Civil Rights Era ended in 1968, or ended at all. The Civil Rights Movement is not a discrete historical period, but an ongoing effort to demand that America live up to the ideals articulated in our founding documents. Dr. King, like Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln before him, insisted that America be not only great, but also good. We need to assess our progress toward that goal, and, in view of the dramatic ways we continue to fall short, work, and not just talk, to make things better.

In Marks and other rural, high-poverty communities throughout Mississippi, we are working to advance a fundamental Civil Right—the right to a quality education. Since 2017, we have been addressing a very specific, yet highly consequential problem: promising students who have the aptitude and work ethic required to excel academically often lack access to the advanced courses needed to achieve their full potential.

Advanced Placement courses prepare high school students for college rigor, enhance admission prospects, and potentially reduce college costs by enabling students to earn college credit prior to matriculation. However, demand for AP classes, particularly in STEM, vastly exceeds the supply of qualified teachers, exacerbating educational disparities that greatly affect future outcomes. University and government studies have found that 95 percent of suburban school districts offer APs, but most remote rural school districts, and most high-poverty schools with substantial black or Hispanic majorities, do not.

In the last three years, we have increased the number of Mississippi public high schools offering AP Physics 1, our inaugural course, by 50 percent. Moreover, in the 30 Mississippi counties (of 82) with the highest school-age poverty rates, our schools are the only ones that offer that course. Prior to our program, Palmer High School, the only secondary school in Quitman County, did not offer any AP courses. It now offers both our AP Physics 1 and AP Computer Science Principles classes.

In his final sermon, Dr. King called for a “Poor People’s Campaign” to march on Washington to press for an end to racism, injustice, and poverty. That Poor People’s Campaign was launched, defiantly, in the weeks after his assasination. Dr. King himself directed that the Campaign begin at Marks, and so it did. On May 14th, 1968, the Marks “Mule Train” started its journey, pulling wagons marked, quite literally, by messages of hope at a time when there were overwhelming reasons for despair—King’s tragic, violent death had triggered convulsive riots that set many cities ablaze.

May 14th, 2020—52 years to the day after the Mule Train left Marks—also marked a significant step forward for that community: every student in Palmer’s AP Physics class took the year-end exam. Even in a typical year, that would be an extraordinary achievement—just one percent of high school students nationally take on that challenge. For the Marks students to dedicate themselves to a rigorous course of study for more than two months after their school closed its doors for the year is heroic. Like the Mule Train participants, those students worked for a better future for themselves and their community. They, too, were animated by hope amidst, once again, great despair. We should heed our students’ example, embrace their hope, and dedicate ourselves to the unfinished work needed for all to share in America’s promise.

A final note: I like to think that I have demonstrated my commitment to the ideals I invoke—several years ago, I left a rewarding career to devote myself to our mission. I also am proud of what we have accomplished and what we strive to achieve. Yet I acknowledge my heart is no bigger than anyone else’s, and my feelings neither validate my views nor justify adding to the tedious torrent of recent corporate commentary that merely checks boxes, recites platitudes, and boosts egos.

If these words are to be helpful, they should illuminate, not emote. In the hopes of doing so, I offer historical context and current data. But presenting our students as the heroic and historically consequential figures they, in fact, are risks depersonalizing them. They are not symbolic figures, but real people with actual names—Dashia, Deonte’, Akira, Myah, and, over the course of our initiative, hundreds of others. They also are teenagers, which means, as every parent knows, they are exuberant, spontaneous, clever, exasperating, befuddling, and, above all, a source of great joy. They each are engaged, in their own way, in the pursuit of happiness our country was founded to, and largely does, permit.

Our actions must always be guided by the knowledge that each of their lives, and the lives of each other person, has meaning, and each has value. And, in the end, that is all we are called to do.

Matt Dolan

Founder and CEO

Global Teaching Project

June 2020